First published by Counsel Magazine in September 2025, in this article I explore how lawyers can engage critically with generative AI – highlighting the challenges of confidentiality and accuracy, and suggesting practical ways to navigate these responsibly in practice.

Neither magic wand nor existential threat, AI is a tool. And like any tool, its impact depends entirely on how we learn to wield it.

Discussions around artificial intelligence (AI) in legal practice are often polarised. Some lawyers believe AI is the future of the profession, set to transform everything from legal research to drafting and case strategy. Others see it as unpredictable, risky and dangerous.

As with most technological shifts, the truth lies somewhere in between. AI is neither a magic wand nor an existential threat – it is a tool. Whether that tool is helpful or harmful depends on how it is used.

Navigating the challenges

AI is evolving rapidly, with new tools emerging daily – each bringing fresh opportunities and concerns. Among the many issues though, two stand out as particularly pressing for legal practitioners: confidentiality and accuracy.

1. Confidentiality

A key concern in legal settings is the potential for confidential or privileged information to be inadvertently shared with an AI tool. Uploading documents or entering prompts without understanding where data is stored or how it might be used can lead to serious breaches.

Just as your professional obligations (and the General Data Protection Regulation) should make you think twice before uploading a confidential document to an online filesharing service without due diligence, you should be cautious about what data you share with any AI tool. In particular, you

need to understand its data handling practices, storage locations and privacy terms.

A recent matter underscores this issue. New Scientist, via a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, obtained ChatGPT records linked to Peter Kyle, the UK Minister for Technology. Among the (benign) queries – such as requests to define ‘antimatter’ and ‘quantum’ – lay a broader lesson: even public officials’ interactions with AI can become part of the public record. However, the response from the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology was limited somewhat by the FOI Act, which only requires the government to disclose information it holds.

For lawyers, the burden is arguably higher. Under the GDPR, clients can make Data Subject Access Requests, which may compel lawyers to disclose not only what information they hold, but also how and where AI was used to process it and who else it may have been disclosed to.

While you might, subject to your records and/or an AI tool’s history settings, be able to advise a client what information of theirs you processed with an AI tool, other questions may prove more challenging, such as:

- Whether personal data was disclosed to other recipients (e.g. through model training).

- Whether any automated decision-making occurred and the logic behind it (which may be difficult as AI tools often operate on a black-box basis).

- How to rectify or delete data if it’s now entangled in a proprietary AI model.

These aren’t merely theoretical questions – they strike at the heart of client trust and regulatory compliance.

2. Accuracy

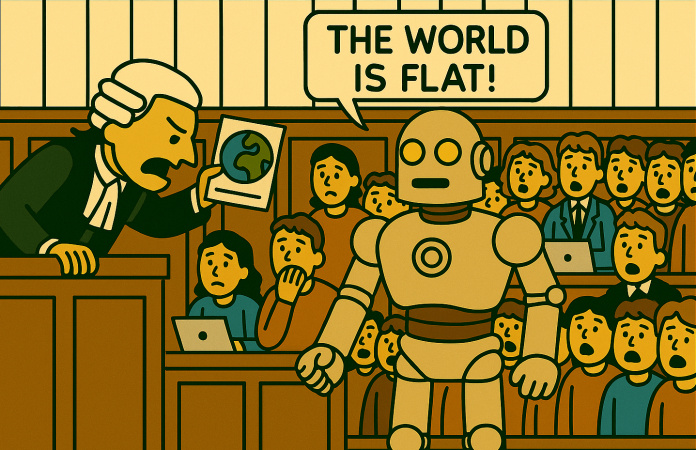

Another core issue is accuracy. Generative AI tools can produce fabricated but plausible-sounding outputs – a phenomenon known as hallucination.

Two recent UK cases illustrate the risks:

- Ayinde, R v The London Borough of Haringey in England [2025] EWHC 1040 (Admin); and

- Bandla v SRA [2025] EWHC 1167 (Admin)

In both, legal representatives relied on fictitious case citations generated by AI in their submissions. In Ayinde, Mr Justice Ritchie reminded practitioners

that ensuring the accuracy of pleadings is their professional responsibility. In Bandla, Mr Justice Fordham imposed a wasted costs order on both the barrister and the solicitors involved.

These rulings reaffirm that while AI can assist, it cannot be relied upon blindly.

Regulatory and ethical considerations

AI is not explicitly regulated for legal practice but existing professional rules remain highly relevant.

The Bar Council has issued guidance on the use of generative AI at the Bar (due for an update but still relevant) that highlights the need for barristers to:

- avoid bringing the profession into disrepute (Core Duty 5) by not submitting erroneous AIgenerated legal research;

- maintain independence (Core Duty 4) by applying their own professional judgement, not deferring blindly to an AI tool; and

- safeguard confidential and privileged information (Core Duty 6 and rule rC15.5 of the Code of Conduct).

The Bar Standards Board (BSB) echoes these points, recommending that barristers think critically about how they leverage AI tools (‘ChatGPT in the Courts: Safely and Effectively Navigating AI in Legal Practice’, BSB, Blog, October 2023).

A practical approach to using generative AI Addressing confidentiality concerns may mean restricting yourself to in-house tools or those with contractual guarantees over data processing.

Even then, developments aimed at reducing hallucinations (such as ‘Retrieval Augmented Generation’) could result in elements of your input spilling into unanticipated domains via background searches conducted to improve output accuracy.

You should therefore check all the settings in the tool and speak to your IT advisers to find out how confidentiality concerns are addressed.

Thereafter, there is a lot you can do to integrate AI into legal workflows more safely and effectively.

I use a structured five-step approach – one I liken to ordering a pizza. This focuses on specifying what I need with precision. (After all, only a brave soul walks into a pizza restaurant and says: ‘One pizza, please.’ Besides a blank/sarcastic look, who knows what you’d get!)

Step 1: Define the task clearly

Set expectations: ‘I need a draft termination clause for a services contract. But let me give you some specific requirements first.’

(Or: ‘I want a pizza. But let me give you some specifics first.’)

Step 2: Set parameters

Clarify the scope of the task. For example, that the clause should allow termination for convenience and be governed by English law.

(Or: ‘The pizza is for two people.’)

Step 3: Provide context

Add detail that might shape the output, such as it being a rolling monthly contract and that the term should favour the service provider.

(Or: ‘I love olives.’)

Step 4: Validate the output

Critically assess whether the output meets your requirements and professional standards.

(Or check: ‘Is it a pizza?’)

Step 5: Iterate and refine

Elaborate each step as needed and reflect on how the tool responds. If at any time it becomes apparent that the tool has misunderstood, correct it before proceeding.

Steps 4 and 5 require real engagement. To support this process, I recommend five additional techniques to help validate and refine the tool’s

output:

- Request citations. Verify authorities exist, are relevant and are correctly applied.

- Ask for a bibliography or list of links. Manually review any external sources to ensure they are established and trusted sources of commentary.

- Ask for a breakdown of how the answer was formed. If any of the steps are assumptions or are unsupported leaps, reject them.

- Stress test the output. Ask the tool to identify the strengths and weaknesses of its output, then verify these for accuracy.

- Explore counterarguments. Start with a neutral form of your query then reframe it from opposing angles or with varied fact patterns to see what emerges.

At each step, see what new authorities and responses are returned by the tool and use these to inform your own judgement, keeping in mind that you cannot delegate legal responsibility to an algorithm.

Conclusion

As highlighted in the BSB’s recent report Technology and Innovation at the Bar, emerging tools like automated drafting, document review, AI-based research and blockchain offer opportunities for transforming legal services – but also carry risks. Lawyers must therefore engage with AI – not by blindly adopting or rejecting it, but by approaching it critically, intelligently and

responsibly.